Juneteenth Is Not Just African American History—It’s African History, Too

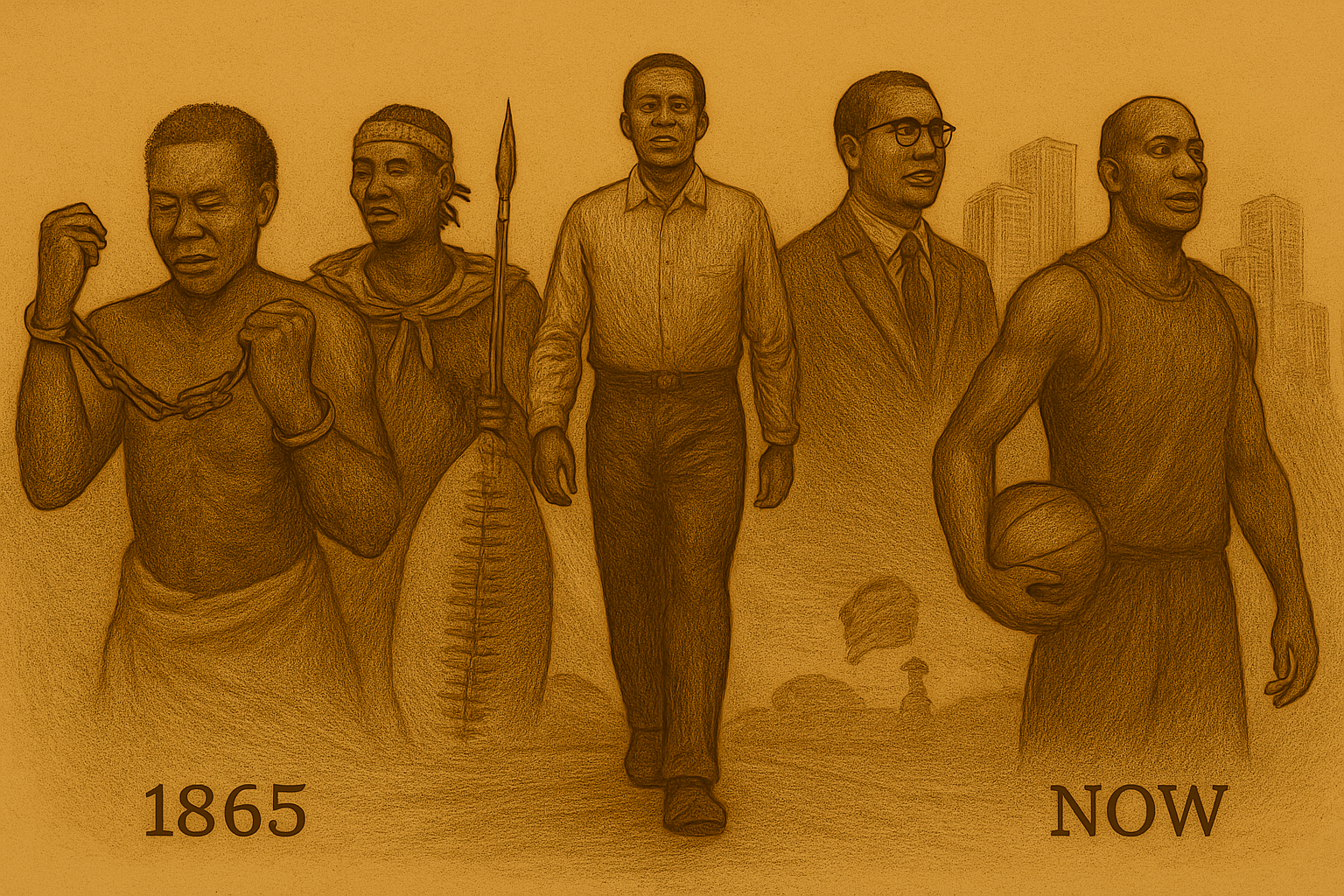

June 19, 1865. On the Gulf shores of Galveston, Texas, nearly two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Union General Gordon Granger arrived with U.S. troops to deliver long-delayed news: enslaved African Americans in Texas were free.

This day would come to be known as Juneteenth, a blend of “June” and “nineteenth.” What started as a local celebration of freedom in Texas grew—over generations—into a national and then federal holiday, recognized across the United States as a symbol of Black resilience, joy, and unyielding hope.

But Juneteenth does not belong only to Black America. Its roots, echoes, and consequences stretch across oceans. To understand its meaning fully, we must begin not in Texas, but along the coasts of Senegal, Angola, and the Congo. Because Juneteenth is not just African American history—it’s African history, too.

The Wound Beneath the Waves: How the Transatlantic Slave Trade Reshaped Africa

From the 15th to the 19th centuries, more than 12 million Africans were kidnapped and trafficked across the Atlantic to fuel the machinery of slavery in the Americas. European traders, with the collaboration of some African intermediaries, built a system that ripped families apart, drained entire regions of their populations, and destabilized thriving kingdoms.

Africa was not simply the place people were taken from—it became the battlefield for a centuries-long war on Black dignity:

Communities were militarized as local leaders armed themselves for defense—or profited from enslavement.

Agricultural systems declined, replaced with economies centered on human trafficking.

Oral histories and spiritual traditions fractured, as generations were lost to ships, chains, and plantations.

This wasn’t just physical destruction. It was psychological warfare. And its aftermath lives on—in disrupted identities, splintered languages, and the global perception of Blackness shaped by centuries of captivity.

Africa, Too, Was a Battlefield in the War for Black Dignity

By the time of Juneteenth in 1865, the legal transatlantic slave trade had already been dismantled by most European powers. But Africa was far from free:

In West Africa, illegal trafficking continued under the radar of European and African authorities.

In Southern Africa, the Basotho Kingdom led by Moshoeshoe I was locked in battle with Boer settlers seeking to dispossess the land.

In Ethiopia, Emperor Tewodros II resisted colonial incursions with modern weaponry and bold reforms—desperate to preserve sovereignty against encroaching empires.

These weren’t peripheral skirmishes. They were parallel resistance movements—occurring while African Americans in Galveston were proclaiming freedom on U.S. soil. The transatlantic struggle for Black autonomy, land, identity, and liberty was being fought simultaneously on both continents.

The Ripple Effect: What Emancipation Meant for Africa

When the last enslaved African Americans in Galveston, Texas, learned they were free on June 19, 1865, the news didn’t echo across the Atlantic with thunder. But over time, the liberation of African Americans would carry deep symbolic and strategic consequences for the African continent—consequences still unfolding today.

Though no ships turned around, and no colonizers loosened their grip, the emancipation of Black Americans created openings in imagination, identity, and global solidarity that reached African shores.

A Symbolic Victory for the Continent

The end of slavery in the United States marked a pivotal shift in that narrative. It challenged the global racial order, offering a powerful message: Blackness and bondage are not synonymous. Though the effects weren’t immediate, the symbolic rupture it caused was seismic.

Africans who had been mourning the hemorrhage of generations found quiet relief in the idea that their kin in the Americas might now breathe freer.

A Pause in the Hemorrhaging

The end of legalized slavery gradually disrupted the infrastructure of the slave trade—already officially banned by many nations but still illegally ongoing. While the European pivot to colonization brought fresh exploitation, it also meant that Africa’s populations were no longer being exported on the same scale. In this space, some regions began to heal—culturally, economically, and demographically.

Seeding Pan-African Thought

Freed African Americans didn't just claim liberty—they redefined freedom for the African world. Their experiences birthed a new generation of thinkers, preachers, and scholars who began to look back across the ocean and ask: What do we owe to Africa? And what does Africa owe to herself?

Mid-1800s: Early Pan-Africanist ideas circulated among African American and Caribbean intellectuals like Martin Delany, Alexander Crummell, and Edward Wilmot Blyden, who emphasized the shared destiny of Africans and the diaspora.

Liberia welcomed some formerly enslaved people as settlers, creating a complex yet symbolic reconnection with ancestral soil.

Later, figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and Kwame Nkrumah would transform Pan-Africanism into a cultural and political movement that influenced independence struggles across the continent.

Juneteenth, in this light, was not just the celebration of an ending—it was the subtle beginning of a Pan-African awakening.

We’d love to hear your thoughts

Do you believe Juneteenth played a role in inspiring or shaping the rise of the Pan-Africanism movement?

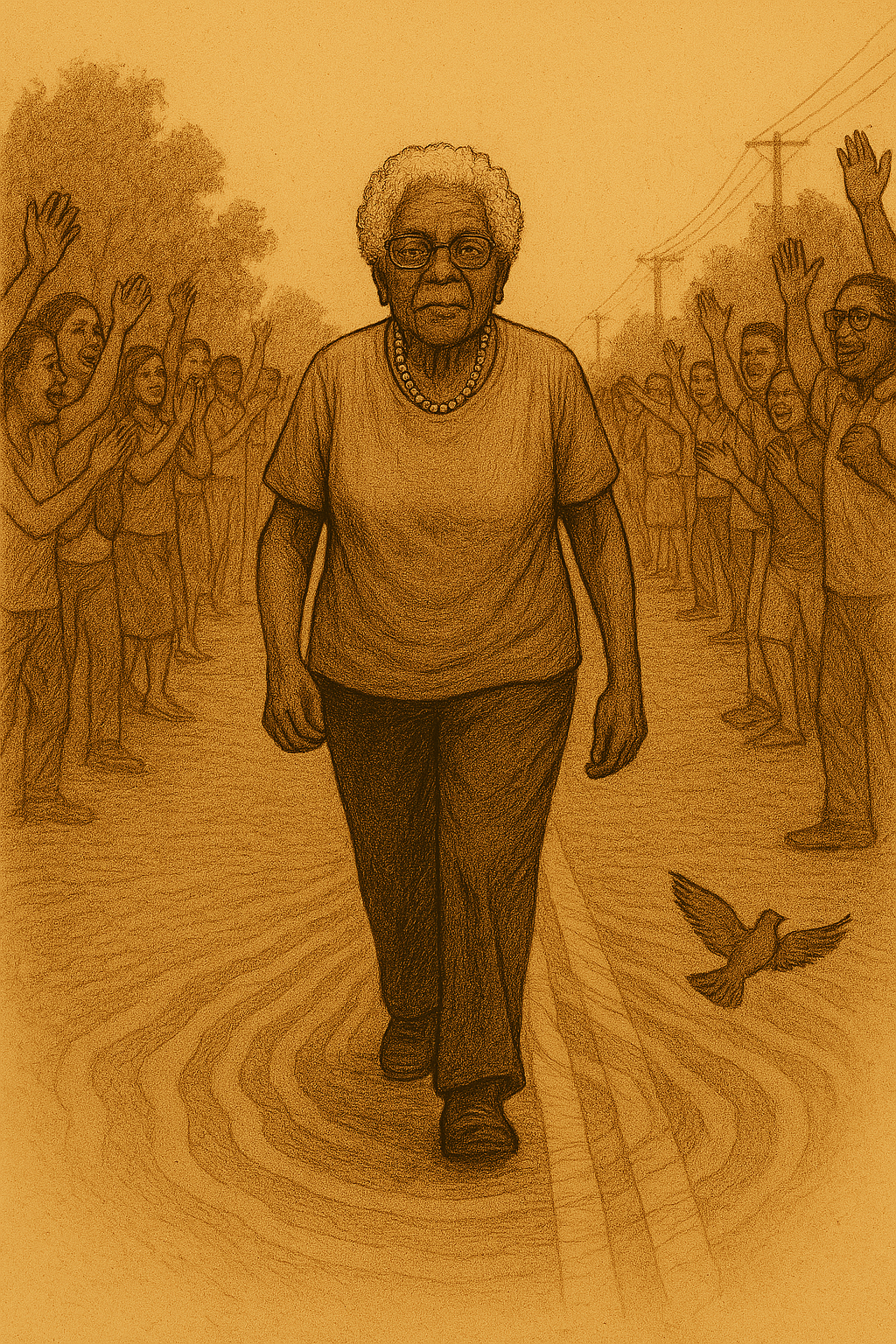

Opal Lee: The Woman Who Made the Nation Remember

No telling of Juneteenth is complete without honoring Opal Lee, the educator and activist who turned a local celebration into a national movement.

Born in 1926 in Texas—just decades after Juneteenth was first celebrated—Opal Lee witnessed firsthand how Black joy could be met with white rage. At age 12, a racist mob burned down her family’s home on June 19. That memory never left her.

Decades later, at age 89, she began a symbolic walk from Fort Worth to Washington, D.C., covering 2.5 miles in each city to represent the 2.5 years it took for freedom to reach enslaved people in Texas. Her activism spanned years of petitions, rallies, and relentless hope.

In 2021, her dream was realized. Juneteenth became the 11th federal holiday in the United States—and Opal Lee was at the White House to witness it.

Through her walk, she not only honored ancestors—she reconnected continents. Her work continues through the National Juneteenth Museum, a forthcoming space of cultural dialogue and remembrance in Fort Worth, Texas.

"None of us are free until we’re all free."

— Opal Lee

"I believe Juneteenth can be a unifier in this country. We have to work at it."

— Opal Lee

"If people can be taught to hate, they can be taught to love."

— Opal Lee

"I don't want people to just celebrate freedom on Juneteenth—I want them to fight for it."

— Opal Lee

Conclusion: The Road Ahead

Juneteenth is not only an American holiday. It is a global echo. A day when voices once silenced by ships and shackles sing again through memory, resistance, and unity.

For Africans, it is an invitation—to reflect, to reconnect, and to renew. To see in the celebration not someone else’s history, but our own entangled struggle. Our own call to dignity.

So when the drums beat and the flags wave on June 19, may they remind us not just of what ended—but of what still must be won.